A seagull stands poised on one webbed foot. Clawed toes grip a granite vantage point in the nautical dawn. I emerge from the path and step out onto the humped back of the fishing rock. Preoccupied with breakfast, if not survival, the gull is indifferent towards me—a skinny kid in a red-and-black Mackinaw jacket. Several other gulls gather to stamp their feet as if in anger on the mossy ground down by the water. Worms mistake the sound of the gulls’ trampling feet for rain and slither up out of the dirt.

Weak chop disturbs the surface of the lake—a slight frown on the water. Clouds in layers slide by, inexorable, the lower levels heavy with rain and passing faster than those higher up. Or so it seems—a parallax view.

Granular snow bits from way up high play in the air, taking fidgety paths down to become a part of the hungry spring lake. I wonder about how long it takes them to fall.

Dad’s still back home in the sack, but old Chester is already here, at his customary perch. He shows me again how to skewer a minnow on the hook. It seems cruel, even with the shiny minnow frozen and long-dead, as the slender brass slips down the throat, out the gill and back in under the salty spine.

Chester speaks with his hands, showing me the hooking technique. The conclusion is all he says aloud: “that’s why the hook is crookt,” he says; just one syllable. “Crookt.” Then he shows me the way to tie the line to the wire leader. His crowned, nicotine-brown fingernails pinch like a snapping turtle beak and pull the knot taut. Chester tugs twice making the line vibrate with a faint musical hum. “See?”

And so, we fish. The depressed economy of words suits us fine. We sit like Buddhas watching the lines angle out, the point where they enter the water constantly shifting and restless. The lead bell weights sit far below, where the bait is held steady, just off the bottom.

Staring with sightless, gelatinous eyes in the gloom, the minnows pose in the milt rich water while wary walleye circle. Our rod tips nod above them like jazz lovers, keeping the syncopated beat of the morning chop while the wind conducts.

The sky gladdens, begrudging every lumen. If you stare at a rod tip too long it goes in and out of focus. Then you close your eyes and a negative image of the tip is projected on the back of your eyelid—a monochromatic memory that fades to black.

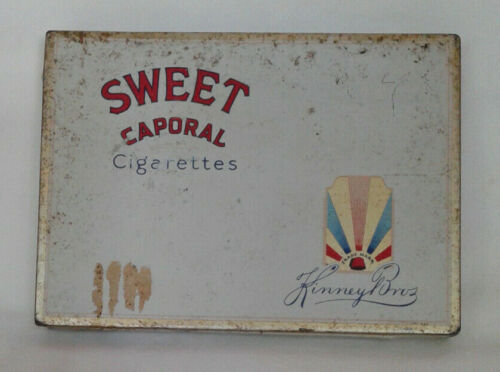

Smoke curls in the air and then invisible hands pull it apart. Chester puffs hollow-cheeked on Sweet Caporal tobacco. As he finishes one, he rolls the next. His fingers look like bratwurst, but their work is adroit. The tobacco smoke reminds me of the city. It smells like summer visits; waiting in the Winnipeg bus depot until I spot Aunty Shirl through the hazy terminal, all sparkling eyes and dimpled face.

“Want one?” Chester asks with a roll-your-own bobbing in the corner of his thin-lipped mouth. He is an unexpected confederate, with me only fifteen years old. I’m small for my age—have not grown out yet.

“How do you make ’em?” I say.

Chester reaches for the pouch and the pad of rolling papers tucked into his parka. Casually efficient, he taps loose tobacco on a square. He twists, licks, and seals then slips the finished cigarette into a breast pocket for later. I catch the scent of the moist, unlit tobacco and I breathe it in. It’s something like fresh raisin bread, right when you open the bag.

I stare at his hands where the dirt is caked into a roadmap of tiny, interconnecting cracks. The look of it is like those pictures of henna tattoos in the National Geographic but wilder; random. It’s from Chester’s world—a place of old friends and dented pick-up trucks with their hoods tilted up on the shoulder of the road. Of full stringers and ducks banking in for a landing, wingtips whistling.

“Now you,” he says, handing me the makings. I snatch a glance towards the path from where Dad might emerge, coming to check on me.

Chester’s eyes offer understanding. A knowing look from a knowing face.

He lays down a round-edged, silver lighter beside me with a tinny click. I copy his technique, roll the cigarette, and lick the glued edge to finish. Just then, my fishing rod twitches. The line draws a sudden, tiny wake where it pierces the surface; a pencil mark etched on the slate top of the water, soon to disappear.

I jump to my feet and scramble down to the dark edge. As I reach for the bucking rod I hear Dad’s big voice behind me, followed by Chester’s nonchalant reply.

I set the hook with a snap and snatch a quick glance back at the two stocky men. There is the cigarette I dropped. It peeks out—just the twirled white tip showing—from beneath the toe of Chester’s rubber boot. The lighter rests nearby, hard to miss.

I study Dad’s eyes but he gives no clue. How long was he there? What did he see? I turn back to the fish and begin to reel.

A minute later I climb up the slope to them with the quivering fish, my hands ice cold from lake water and flecked with clinging fish scale. I don’t know what to say.

Chester sits with a crookt smile on his face. There are crow’s feet at the corners of Dad’s eyes and his amused gaze pecks and probes.

“Breakfast, kiddo. Bring your fish,” he says, his head cocked. “We’ll smoke it later.”

“Sweet Caporal” is published on TOEWS.IR by special permission of the author, Mitchell Toews, who holds the copyright.